Real Wage Growth: The Post-Pandemic Labor Market and Beyond

Are wages still growing? And what about wage compression?

It's been a little while since I've written about real wages. In that time, the labor market has cooled down somewhat, with unemployment creeping up from the lows we saw during the post-pandemic recovery. What has this shift meant for real wage growth, especially for middle- and low-income earners? Let's take a look at the data to see how the current economic environment has affected wages, particularly for non-managerial workers.

Real wage growth and compression

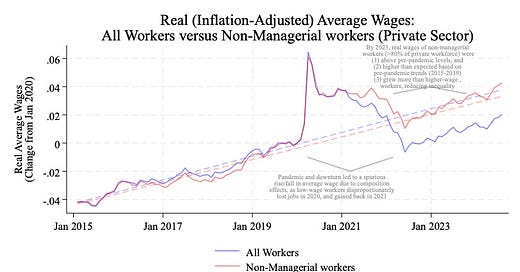

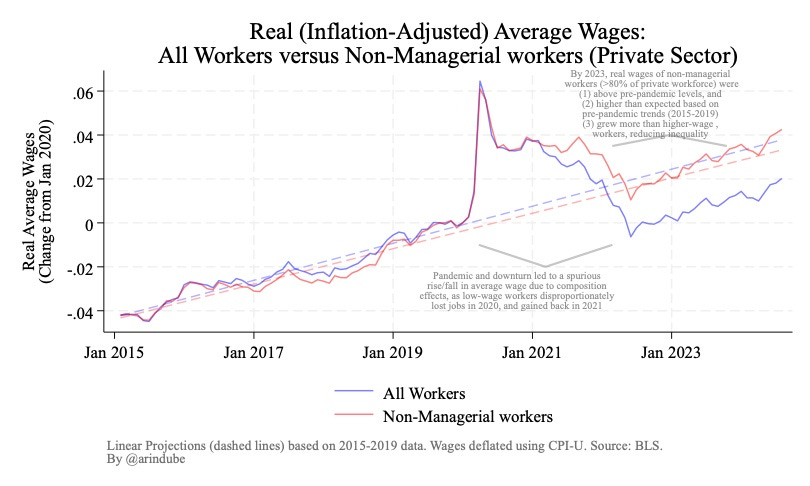

The chart comparing real (inflation-adjusted) wages for all workers and non-managerial workers from 2015 to 2024 reveals insights into the labor market dynamics of the past several years. Both groups followed a similar trajectory before the pandemic, with steady but modest wage growth. However, the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted this trend in a dramatic way.

In early 2020, the chart shows a sharp increase in wages. However, this spike is largely attributed to composition effects—lower-wage workers, who were disproportionately laid off during the early stages of the pandemic, caused the average wage for the remaining workers to rise. When many of those low-wage workers re-entered the workforce in 2021, the average wage dropped, but still remained above the pre-pandemic trend. By end of 2021, most of this composition bias had resolved itself as workers re-entered.

The post-pandemic recovery was marked by continued tightness in the labor market, driving wages for non-managerial workers beyond pre-pandemic expectations. This is especially evident in the data for 2021-2023, where real wage gains for non-managerial workers exceeded those of all workers. In fact, wage growth in this group slightly outpaced projections based on pre-pandemic trends (between 2015 and 2019), reflecting the intense demand for labor in low-wage sectors that increased competition and reduced monopsony power. These trends suggest that tight labor markets helped reduce wage inequality, as employers had to raise wages to attract and retain workers in non-managerial roles, which make up roughly 80% of the private workforce.

Even as the labor market has cooled somewhat over 2024, and unemployment has climbed above 4%, real wage growth has been strong, and the reduction in inequality has persisted.

Taking a Step Back: A Long-Term Perspective

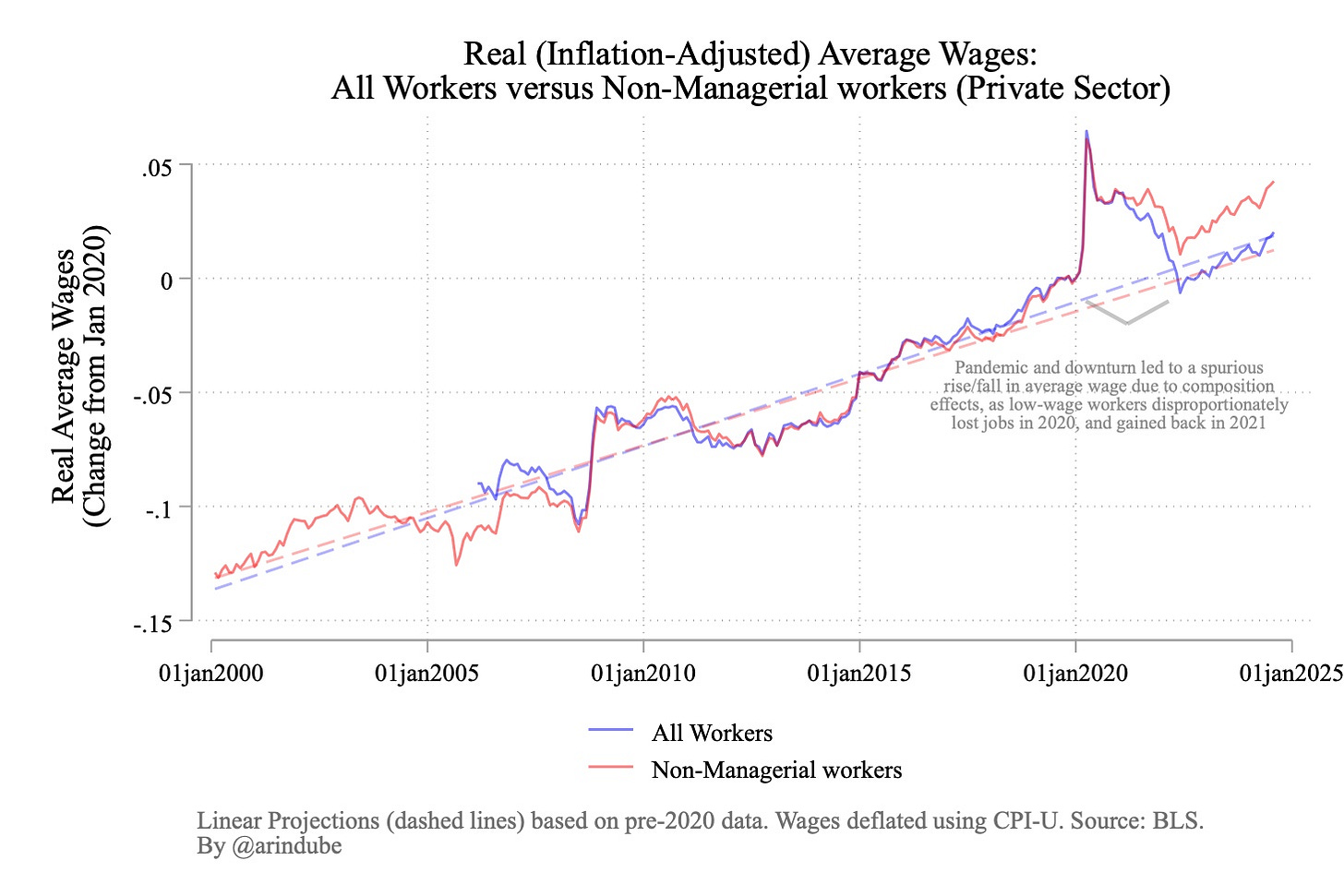

To better situate these trends in a broader historical context, we can step back and look at a longer period, as shown in the chart for real wages of non-managerial workers from 2000 to 2024. This perspective underscores just how significant the wage growth has been in the post-2017 period, especially when compared to the stagnation that defined the earlier part of the 2000s.

Between 2000 and 2017, real wages for non-managerial workers grew slowly, with little deviation from a relatively flat trajectory. However, from 2017 onward, as the labor market tightened, wage growth for this group became much stronger. Also note that if we consider the wage trends for a longer period—as we do in the figure above, in contrast to the earlier figure—it suggests that overall real wages are today at trend, while non-managerial wages are above trend. This is another illustration of the fact that wages have grown faster after 2017.

Despite the disruptions caused by the pandemic and the burst of inflation in 2021-2023, real wage levels remain well above pre-2017 trends. The fact that real wages have continued to rise, even in the face of inflation, is a testament to the power of full employment in driving wage gains.

Conclusion

The post-pandemic labor market has been shaped by unprecedented challenges, yet it has also created an environment in which workers—particularly non-managerial workers—have seen real wage growth that outpaces historical trends. This period of tight labor markets and full employment has demonstrated that strong labor demand can significantly boost wages, particularly for lower-paid workers. Looking ahead, maintaining this momentum in a post-pandemic economy will be essential for sustaining these gains and ensuring that wage growth benefits workers across the income spectrum.

Are you not concerned that BLS does not do wage indexes but only remuneration unit value indices? If not, why am I wrong to be concerned?

Yes, looking at the Consumer Expenditure Survey, real per capita income under Biden was well above Trump and Obama. 2006 though, was almost as high as 2021-2023