Competition and Concentration Are Not the Same

We want more competition, and sometimes that may entail more concentration

In recent years, we've seen a significant increase in antitrust activity, particularly from agencies like the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), led by Chair Lina Khan. This renewed vigor in addressing monopolistic practices dovetails with growing concerns about market power, both in product and labor markets. This is a welcome development. We all benefit from a more competitive marketplace, whether as consumers buying products or workers selling labor.

However, it’s important to distinguish between competition and concentration. While we should discourage less competitive markets, higher concentration doesn’t necessarily signal reduced competition. In fact, sometimes, competition can lead to higher concentration—particularly in labor markets. Let’s unpack why.

Why Competition Can Increase Concentration: A Labor Market Perspective

There are many sources of monopsony (employer market power) in labor markets. One common reason for monopsony power is concentration—too few employers hiring workers in a particular market. But there are other factors as well, including “search friction,” where workers find it difficult to locate and switch jobs, or the fact that different workers may value jobs differently based on location, schedule flexibility, or other preferences. These factors give employers some ability to set wages below what they might pay in a perfectly competitive market.

At the same time, employers also vary in their productivity. Higher productivity employers tend to pay higher wages to attract and retain workers. But if there’s limited competition, fewer workers can climb the “job ladder” to these better-paying employers. This was the case in the U.S. after the 2007-2008 financial crisis, when wage growth and mobility were sluggish, and many workers stayed stuck in lower-paying jobs.

When Competition Heats Up

Starting around 2018, and particularly during the tight labor markets of 2021-2022, competition for workers increased. Workers began moving to better-paid positions, and competition between firms intensified. Here’s where the distinction between competition and concentration becomes important: even as competition for workers grew, concentration increased as well. Why? Because higher-paying, more productive firms were able to recruit more workers, while lower-wage, less productive firms struggled to compete.

In my recent work with David Autor and Annie McGrew, we explored this dynamic in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic. We found that increased competition—driven by a tight labor market—was likely behind the sharp rise in wages at the bottom of the pay scale. Higher productivity firms could offer better wages, while lower productivity firms faced difficulties retaining workers. As a result, employment shifted toward higher-paying employers, increasing concentration even as competition improved the lot of workers across the board.

Evidence From the Data

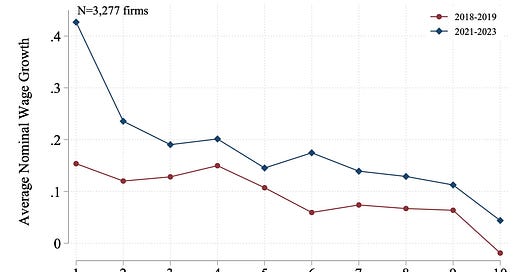

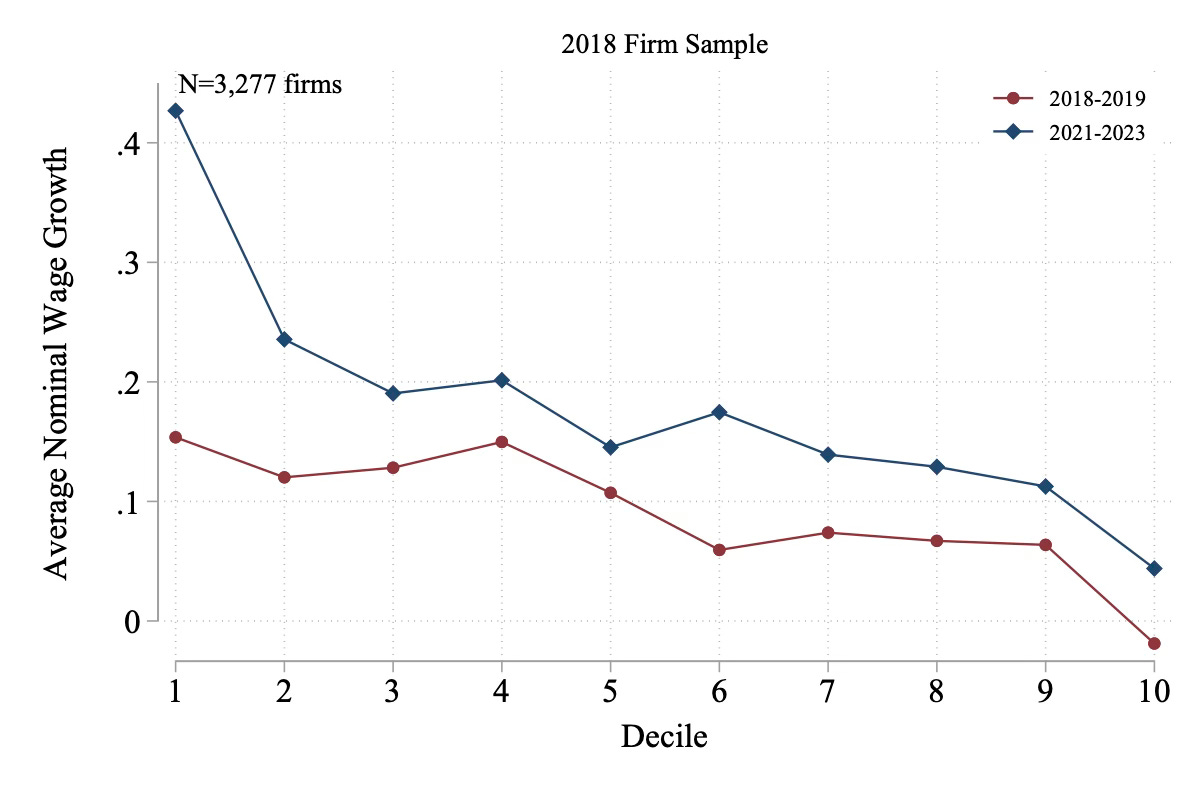

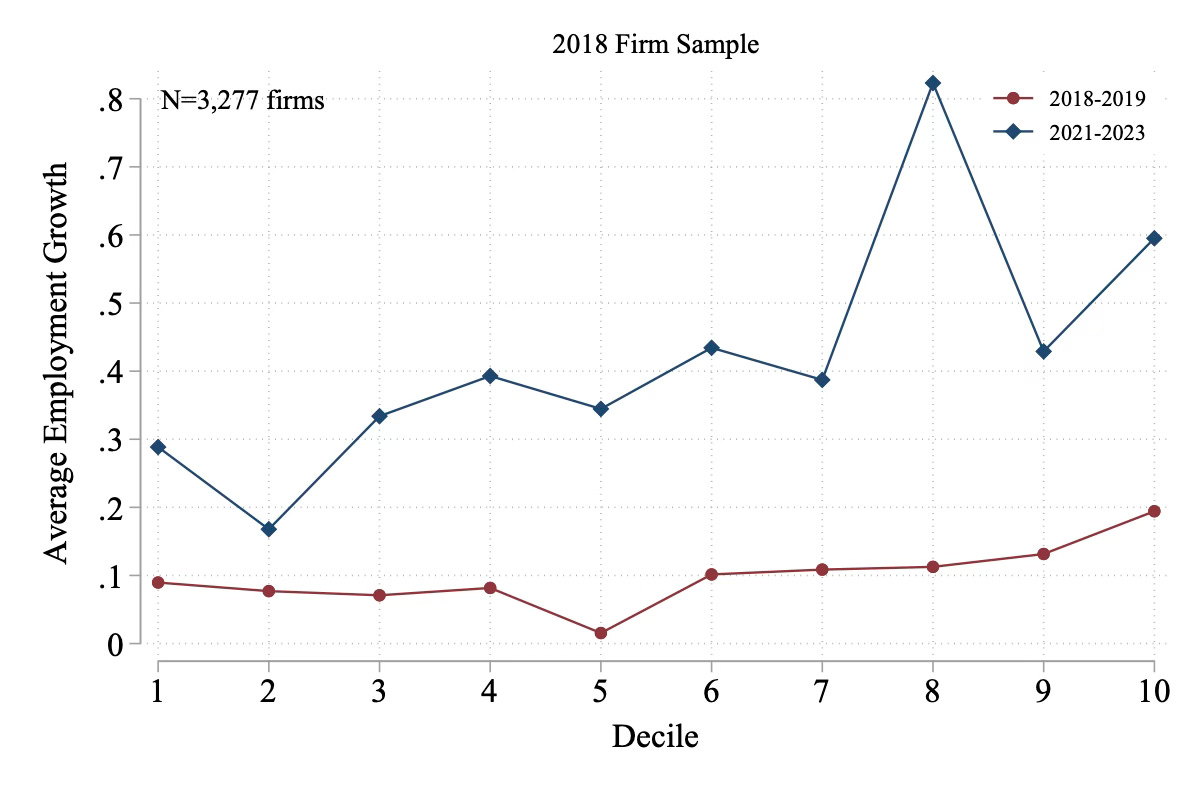

Let’s turn to some data. Recently, using private payroll data from a sample of employers using a major payroll processor, we analyzed firm-level wage and employment growth in the low-wage sectors of the economy: retail, accommodation and food services, and arts, entertainment, and recreation.

The data in the first figure shows that firms historically paying the lowest wages (in the bottom decile) saw the sharpest wage growth during the 2021-2023 period—a clear sign of increased competition for workers.

But at the same time, as the second figure shows, these lower-wage firms struggled to grow employment. Instead, higher-wage firms (likely more productive employers) were the ones expanding employment during this period. This is a signature of a more competitive labor market, as workers moved to better-paying firms as vacancies expanded, and the market tightened.

This stands in contrast to the patterns we saw before the pandemic, where wage growth and employment were relatively more comparable across deciles of firm pay.

What Does This Mean?

The takeaway is that while the post-pandemic competition led to higher wages for workers, it has reallocated workers to better-paying, more productive employers. This has likely fueled some increase in concentration, but that’s not something to fear. In fact, it’s a cause for celebration. It suggests that the labor market is becoming more competitive, and workers are being rewarded with better wages and opportunities at more productive firms. Interestingly, a similar pattern arises after minimum wage increases, where a higher wage floor can lead to reallocation to more productive enterprises.

The beneficial role of tight labor markets cannot be understood just with simple models of supply and demand (“it’s not only a labor supply or labor demand shock”); it requires an understanding of labor market competition. But this also highlights another crucial fact: competition and concentration are not the same. And, at times, more competition can actually drive higher concentration—but in a way that benefits workers and the economy as a whole.

I found your writings